Thinking is a very human activity, isn’t it? A gift, some would say. An essential developmental characteristic we have been given, others would say. After all, “We Think, Therefore We Exist. Or, at least, that is what we have been believing for centuries. Pretty obvious, right? Thoughts seem to exist to be thought, and our mind seems to exist to think those thoughts. Simple enough. So, if this characteristic is what makes us human, how is it that thought can become a weapon of mass self-destruction? How is it that something so “ours” by default, can become so detrimental to our well-being, even to our sanity? Do you think this is an exaggeration? Keep on reading!

Obviously, we need to think many kinds of thoughts in order to function and be operational in our daily lives: shopping lists, to-do lists, work and home reminders, school projects, appointments, college assignments, life considerations, future steps, risk analysis, artistic creations, relevant decisions…we are constantly thinking thoughts that help us deal with our lives on a daily basis, and those thoughts are perfectly useful. When we think these thoughts intentionally, the feeling we get is one of direction, purpose, control, and motivation.

Obviously, we need to think many kinds of thoughts in order to function and be operational in our daily lives: shopping lists, to-do lists, work and home reminders, school projects, appointments, college assignments, life considerations, future steps, risk analysis, artistic creations, relevant decisions…we are constantly thinking thoughts that help us deal with our lives on a daily basis, and those thoughts are perfectly useful. When we think these thoughts intentionally, the feeling we get is one of direction, purpose, control, and motivation.

On the other hand, we also often think thoughts that help us escape from our lives, such as fantasies, cravings, expectations, memories, daydreams, premeditations, assumptions and evaluations. We spend a great deal of time going back to the past or forward into the future, lost in thoughts that have little to do with what is happening here and now.

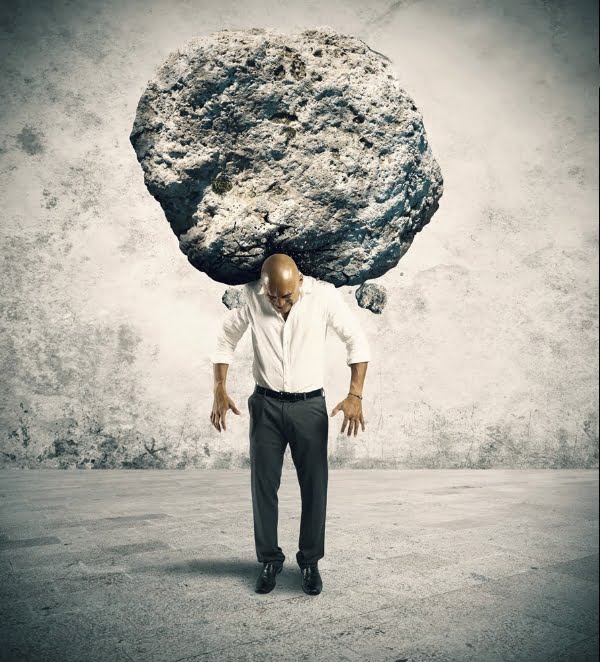

What we most often do, however, is spend time thinking about what we colloquially call “self-blaming”: reproaches, self-deprecation, self-criticism, self-devaluation, guilt thoughts….Unlike the more benevolent or neutral thoughts that we may sometimes think, these types of thoughts can cause a lot of harm to our well-being, for they undermine our self-image, make us feel guilty or inadequate, and build an image of ourselves that is far from kind.

What we most often do, however, is spend time thinking about what we colloquially call “self-blaming”: reproaches, self-deprecation, self-criticism, self-devaluation, guilt thoughts….Unlike the more benevolent or neutral thoughts that we may sometimes think, these types of thoughts can cause a lot of harm to our well-being, for they undermine our self-image, make us feel guilty or inadequate, and build an image of ourselves that is far from kind.

But the most important thing is that all these thoughts, whether harmless or harmful, past or future, true or false, they all take us to places that, in reality, do not exist, and contribute to create an image of someone we are not, or only partially are. And despite this, they seem totally real to us and we believe them at face value. And where is it that we feel their reality? Exactly, in the body. Through the emotions that arise and are felt in the body. And this is how we connect thoughts to emotions. For a long time, there has been – and still is – a debate as to which comes first, if thoughts or emotions. Generally speaking, experts agree that emotions are the result of our evolutionary and neurobiological development,  an adaptive feature that helps us to take action when a need arises that demands to be satisfied, and their functionality would depend on the effective interaction between emotion and cognition. Looking at them from this perspective, we can assume that emotions precede both action and thoughts, since the adaptive response would be impulsive, even automatic, as when we immediately withdraw our foot if someone steps on it. Yet life is never simple. At least not for sentient and thinking beings.

an adaptive feature that helps us to take action when a need arises that demands to be satisfied, and their functionality would depend on the effective interaction between emotion and cognition. Looking at them from this perspective, we can assume that emotions precede both action and thoughts, since the adaptive response would be impulsive, even automatic, as when we immediately withdraw our foot if someone steps on it. Yet life is never simple. At least not for sentient and thinking beings.

So “We think, therefore we exist” could be interpreted more like “We think, therefore we feel”. When we think about something, this something becomes absolutely real for us. And the way it becomes real for us is how the thoughts we think make us feel in our bodies.

Let us test this affirmation. Try this: close your eyes and think of your favorite place to relax on the beach, in the mountains or in a forest. Listen to the sounds, smell the aromas, feel the temperature, the breeze. Then check how you feel. Now, think about the last time you had a serious disagreement with someone you care about, a sad disappointment in a friend, or a feeling of guilt due to something you did to someone. Bring to your mind the situation, the emotions you felt at the time, and the outcome. Check how you feel right now. As difficult as it might be for you to perceive sensations through your mere thoughts, it is very likely that you are able to feel different feelings in your body during the exercise, depending on what you are bringing to your mind. In fact, what all the scenarios in the above exercise have in common is that none of them are happening right now. None of them are real. They are just images, ideas and memories in your mind. They are just thoughts that you are thinking. Now, imagine that you are in front of the mirror, looking at your own image. What thoughts come to mind about yourself? How do you feel when you look at your reflection? What do you think it is -if you are able to identify it- that makes you feel this way?

This simple exercise teaches us that the rationality we usually rely on is not entirely reliable. Not at all. Even a “healthy” mind does not always contain the truth and nothing but the truth about ourselves and about our world. Conversely, it may contain hundreds of invented thoughts, or thoughts that are mere echoes of distant memories and events, which do not even exist anymore in the present moment. This is the enormous impact of our thoughts on our emotional state. And, if half of the thoughts we have per day are negative thoughts about ourselves or others, what kind of emotions will we then feel on a regular basis? After reading all of the above, you can probably understand why meditation and mindfulness are so popular in humanistic psychotherapy settings. The notion of an uncontrolled mind that can become a means of massive self-destruction, and the need to see through it and learn ways of reining it in, is the cornerstone of many therapeutic approaches such as Gestalt Therapy, Systemic Psychology, Existential Therapy or even CBT (Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy), among many others. Our mind can be of great use to us, yet it can also be extremely harmful. It all depends on whether it is we who use our mind, or the other way round.

The notion of an uncontrolled mind that can become a means of massive self-destruction, and the need to see through it and learn ways of reining it in, is the cornerstone of many therapeutic approaches such as Gestalt Therapy, Systemic Psychology, Existential Therapy or even CBT (Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy), among many others. Our mind can be of great use to us, yet it can also be extremely harmful. It all depends on whether it is we who use our mind, or the other way round.

Every time we think a thought, without realizing the consequences it is having on our emotional state, we are being used by the mind. Not that the mind is wicked per se. The mind simply does its thing. But letting it run wild, without us being fully aware of what it is doing, can have a huge impact on our body, our emotions, and yes, even our own mind. Stress, rumination, obsessive thoughts, irrational fears, low self-esteem, self-doubt, are all the result of thoughts – any kind of thoughts – that are thought without any control or awareness, thoughts that trigger the consequent emotional reactions.

How can this even happen? Because we give total credit to what our mind says. For us, the mind is the ultimate oracle and knower, the goddess of our system, the revered master of ceremonies of our lives, the height of wisdom. We have been taught to worship and abide by it since we were children, and we do so without question.

Gestalt psychotherapy, meditation, Mindfulness or conscious awareness tools, all invite us to question this alleged truth. While meditating or practicing mindfulness, or while deepening our understanding of how our mind works through psychotherapy, the whole thought-emotion-reaction chain is momentarily deactivated, which allow us to gradually learn not to pay so much attention to our thoughts. Or rather, what we learn is not to believe everything our mind thinks. And this, as simple as it may seem, is key. Because when we stop believing everything our mind tells us to, we can begin to question how we relate to ourselves and to others, how we treat ourselves, how we expect others to treat us, and most importantly, we can decide what we want to believe about anything, and what we don’t. In other words, we cease to be slaves of our mind, and we both become life companions. This is, in fact, the beginning of liberation. If you want to start changing the way you relate to your mind and thoughts, book a free 20-minute online interview by clicking here. References Izard C. E. (2009). Emotion theory and research: highlights, unanswered questions, and emerging issues. Annual review of psychology, 60, 1-25. Pics: @celiaroblesteigeiro y @elisabetaranda

This post is also available in:

![]() Español

Español